City Hearing Officer Deals Fatal Blow to Crackdown on STVRs in Residential Districts of the Hermosa Beach Coastal Zone

HERMOSA BEACH, CA – In a far-reaching ruling, a city of Hermosa Beach administrative hearing officer earlier this month tossed out a code enforcement citation issued for what city code enforcement claimed were unlawful short-term vacation rentals (STVRs) at the Vurpillat, a 28-unit, historic building on Hermosa Beach’s popular Strand. The ruling issued in an appeal from the citation, filed by Jay Mitchell, the Vurpillat’s owner.

In 2016, the Hermosa Beach city council passed an ordinance blanketly banning STVRs in all the city’s residential districts. The Vurpillat is in a residential district (R-2). It is also located in the California coastal zone and is instrumental in offering beach access for South Bay locals and vacationers alike, at affordable overnight rates compared to local hotel rooms and single-family homes.

Last April, the council doubled down on its crackdown on STVRs, decreeing steep increases of the fines imposed against hosts and guests: $5,000 for the first violation, $10,000 for the second, and $20,000 for the third.

In the appeal, Angel Law, Mitchell’s legal counsel, successfully argued that the California Coastal Act of 1976 prohibits the city from enforcing its ban on STVRs in properties located in the coastal zone. Agreeing, hearing officer Steve Napolitano ruled that under the Coastal Act, “the City was required to submit a CDP [coastal development permit] to the [California] Coastal Commission for approval prior to implementing the City’s prohibition on STVRs in the coastal zone. Because the City failed to do so, the City’s prohibition of STVRs in the coastal zone is invalid and does not apply to the Property in this case.” The hearing officer thus dismissed the citation and ordered the city to refund Mitchell the $5,500 fine it had forced him to pay.

While code enforcement targeted the Vurpillat with citations based on the illegal STVR ban, at the same time, it ignored publicly available evidence that this landmark oceanfront apartment hotel has functioned in the same manner for over 100 years on the Hermosa Beach Strand. It was built in 1923. When code enforcement’s authority to shut down STVRs at the Vurpillat was questioned, rather than agreeing to meet with and hear out the owner, the code enforcement officials retaliated with another citation the same day — the citation that ultimately led to the appeal hearing and the STVR ban being declared unenforceable.

“I never set out on a mission to sue the city to overturn their illegal STVR ban in the coastal zone, but rather wanted to be left alone to continue to operate legally in the complaint-free manner as the Vurpillat has been operating for 101 years now,” said Mitchell. “The code enforcers’ inexplicable refusal to sit down for a constructive meeting to resolve this dispute without the unjustifiable fine and dragging me through a protracted hearing process is what led to the city’s defeat. Quite simply, they overplayed their hand. This was all avoidable had the city been willing to listen, communicate, and follow the law.”

This decision in favor of Mitchell, which beat the path for another decision issued just two days ago, dismissing a citation against another property owner in the Hermosa Beach coastal zone, sounds the death knell for the city’s sweeping STVR ban in the coastal zone. According to Frank P. Angel, Mitchell’s lead counsel, this ban is unenforceable not only because the city never received approval for it from the Coastal Commission; also, it violates the Coastal Act’s mandate for public access to the shoreline. Angel is confident that the Coastal Commission will never approve it. The Coastal Commission put the city on notice as early as 2016 that in light of the Coastal Act’s requirement for maximum public access to and along the coast, blanket STVR bans will not pass muster.

“Hermosa Beach may not stay the course of excluding thousands of annual visitors from overnight access to the coastal zone under the color of an ill-advised municipal ordinance that flouts state coastal law and discriminates against outside visitors,” said Angel. “Earlier this year, we warned that city officials were playing with fire,” Angel added. “If you play with fire, you’ll get burned.”

Hermosa Beach’s STVR ban denied short-term residency in the coastal zone to anyone who couldn’t afford to rent a house or an apartment for at least 30 days. And if those restrictions weren’t drastic enough to keep nonlocals out after sundown, the ban forbade renting even just a single room by the beach for a night or so.

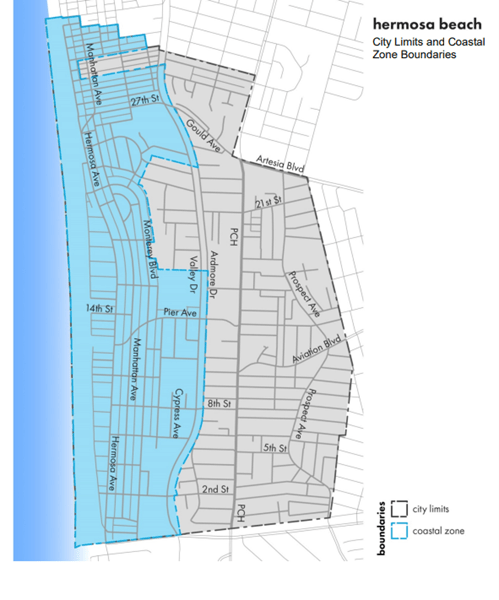

The Hermosa Beach coastal zone extends approximately 1,000 yards inland from the coast. The decision affects almost half of the city’s incorporated territory, as depicted on this map:

Of note as well, the hearing officer also rejected a false charge fabricated by code enforcement that the property was being illegally operated as a “hotel” in a residential zone. The hearing officer reasoned: “The City offered no evidence to show the City’s code ever expressly prohibited STVRs prior to adopting its 2016 prohibition . . . . Under Keen [v. Manhattan Beach], it is irrelevant whether the Property’s units were exclusively rented for more or less than 30 days if there was no textual distinction between the two in the City’s codes. As also stated in Keen, ‘Use of the word “residence” does not imply some minimum length of occupancy.’ Thus, it cannot be implied that Appellant is operating the Property as a hotel based on the length of a stay or residency.”